INTRODUCTION

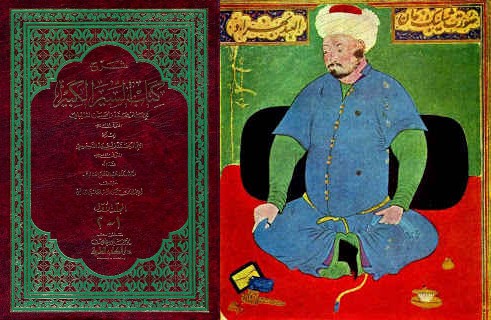

Fiqh al-Siyar is usually described as “Islamic international law.” In classical literature, scholars usually describe fiqh al-siyar as the legal rules regulating how the Dar al-Islam (Islamic nation) interacts with other nations, although some specify the definition to include only war. These classical works, such as Imam Shaybani’s (d.106 H) Siyar al-Kabir, is dominated by the laws relating to the conduct of warfare. However, laws relating to peace are also discussed such as rulings related to trade, diplomatic envoys, etc.

As a branch of fiqh (Islamic law), fiqh al-siyar takes it source from the Qur’an, Sunnah, Ijma, and Qiyas. However, as noted by Majid Khadduri (1966), fiqh al-siyar also takes note of international treaties and reciprocity. As explained by Jack L Goldsmith and Eric A Posner (2005), large scale reciprocity becomes a customary international law. However, these sources can only be accepted to the extent that they do not contradict the primary sources of Islamic law.

DEVELOPMENT IN THE MIDDLE AGES

Much have changed as time goes by. One development worthy of note is the emergence of multiple Islamic nations, after the first centuries after the death of Prophet Muhammad PBUH witnessed only one Islamic nation. Classical jurists like Imam Al-Juwainy (d.478 H) noted this development and argued how there can be multiple leaders of the Muslims if necessity dictates so.

Another development with profound implication is the advent of the Western (European) civilization. The most obvious result of this was colonialism towards much of the world including most of the Islamic world. Numerous Islamic nations had their Islamic systems dismantled and replaced by colonial laws, such as what happened to the Islamic kingdoms in the Nusantara (Ramlah, 2012).

However, a very important result of Western colonialism was hegemony. Economical and political hegemony was one issue, resulting in neocolonialism, meaning that ex-colonies dependant towards the European States. Another more impactful hegemony was that of knowledge and culture (Wan Mohd Nor Wan Daud, 2013).

As Muhammad Naquib al-Attas (1993) argues, the Islamic and Western Civilizations are the strongest contenders in the claim of universalism of values that they promoted. Muslims believe that Islamic values are universal as they are revealed by Allah Himself, and conveyed by His prophets. However, Muslims spread Islam with peaceful da’wah (propagation) because “there is no compulsion in religion”. As numerous scholars have noted, Muslim conquests do not translate into compulsion of religion.

On the other hand, Antony Anghie (2004) explains how the Europeans imposed what they conceived to be the (universal) natural law through a ‘civilizing mission’ by the ‘civilized nations’ and ‘uncivilized nations’. This was the legal justification for colonialism which could be found in the works of the widely acclaimed ‘fathers of modern international law’ such as Fransisco de Vitoria, Hugo Grotius, and Emer de Vattel.

Anghie observed that colonialism was the foundation of modern international law. And, together with that, as I have argued elsewhere, secularism was imposed as a standard of ‘civilized’ and knowledge.

MODERN DEVELOPMENTS AND THEIR IMPACTS

All of the aforementioned developments in the middle ages resulted in further developments in the modern day to create the current state of the world in need of an important development of fiqh al-siyar.

First, there are numerous Muslim majority states but in form of the nation state model, and perhaps only a couple of them resemble a proper Islamic nation in terms of structure and legal system (Saudi Arabia, Brunei Darussalam, Pakistan, arguably). Therefore, in reality, their participation in international law typically would not take heed of fiqh al-siyar (or Islam at all). Their legal systems would usually not give room for that, except for maneuvers which are claimed to be ‘consistent with Islam’ (but not necessarily so except occassionally by coincidence).

Second, post World War II, the world is as if organized as a “global village” under the United Nations. “As if” is because it is not exactly like a government per se, as states still retain their sovereignty and the UN does not claim to be a World Government. But the United Nations holds a central role in the conduct of international relations, functioning in many ways similar to a government. For example, the UN conducts treaty facilitation, dispute resolution, policy, and most (in)famously: security enforcement. Therefore, to some extent, the UN is shaping a world similar to that of a global village with the UN as Chieftain. Additionally, the trend of inter-state warfare has much reduced since pre-world wars (this is notwithstanding the existing bloody armed conflicts which are mostly non-international).

Third, the medieval law trend of “universal international law” is preserved through a mix of constructivist and positivist trends of international law making. Many multilateral international treaties are made with the intention to bind as many states as possible. Additionally, Alan Boyle and Christine Chinkin (2007) have written how international law can be constructed via various means. Among them, albeit soft laws not being formally binding, they can be very effective in shaping uniformity of state practices towards the making of customary international law. It is noted that regionalization is also a trend in the past few decades, but it does not negate the trend of the making of a general international law.

Fourth, international law has evolved to also regulate how states handle their internal affairs, after previously only regulating international relations. Malcolm Shaw (2006) notes that this important development was most noticeable in the advent of international human rights law. Therefore an intersection between international law and constitutional law appears. When conceded to, international law is binding to states generally regardless of national laws. On the other hand, internally within the state, governments are also accountable towards their people and/or constitutions. This is why there are discourses on the position of treaties within national law systems.

FIQH AL-SIYAR AS A FILTER TO MODERN INTERNATIONAL LAW?

Having all that said, much thought needs to be placed upon the state and fate of fiqh al-siyar in this contemporary world.

There is even much discourse on what the form of the Islamic nation should be. Some scholars argue in favor of a modern kind of caliphate such as Taqiy al-Din Al-Nabhani (2002), others are content with a “Darus Salam” model like Indonesia (Afifuddin Muhajir, 2017), some indulge in discourse on the extent to which democracy could be accepted as discussed by Rapung Samuddin (2013), and there are more discourses. This discourse certainly affects whether the states could classify as Dar al-Islam, in turn affecting their rights and obligations in fiqh al-siyar.

This is not to add the other problems on how the Dar al-Islam should position itself. Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi (2005), an Al-Qaeda affiliated scholar, wrote how Saudi Arabia’s membership to the UN is among the reasons why it is not an Islamc State. Al-Maqdisi argued that such membership means that Saudi Arabia has submitted itself under the leadership of non-Muslims and under a non-Islam legal system.

Al-Maqdisi’s argument is mostly misplaced. It is correct that submitting oneself under the wilayat (patronage) and believing non-Islamic laws as better than Islamic ones are among the nawaqid al-Islam (nullifiers of Islam). However, the UN is neither legally nor structurally a “patron” for its members. Even the UN Court (i.e. the International Court of Justice) cannot adjudicate a dispute without the parties agreeing to do so, and Saudi Arabia has never agreed to this. Additionally, the UN formally binding laws are mostly either treaties or customary laws, which are both recognized sources of fiqh al-siyar.

However, parts of the reasoning of Al-Maqdisi’s critic is worth pondering further. The shaping of customary laws can be directed by UN bodies (some consisting only by a few states) as argued by Boyle and Chinkin (2007), and this might, to some extent, be considered as “tawalli” (patronage).

Additionally, only treaties and customary laws which do not contradict the Shari’ah may be participated in. Some Muslim states have been careful in this, occassionally making reservations to parts of treaties so that the un-Islamic parts are not binding but the other parts can be taken. This is most obvious in international human rights treaties which are usually partially reserved by Muslim majority states such as Malaysia and Saudi Arabia.

However, even considering efforts to ‘maneuver’ with reservations, some scholars including Umar Ahmad Kasule (2009) argue that human rights are fundamentally un-Islamic. If we accept Kasule’s argument, which would admittedly take some serious and committed reading to fully grasp, then all human rights treaties are un-Islamic irrespective of their reservation.

Therefore, much effort must be dedicated to examine all forms of the international law making process from an Islamic standpoint.

FIQH AL-SIYAR AND THE MAKING OF INTERNATIONAL LAW

Even further, fiqh al-siyar should not only develop in a defensive manner by filtering out un-Islamic content from affecting the Muslim nations as per the previous section. Rather, fiqh al-siyar should start to also discuss how Islam can contribute or even take a leading role in the making of international law.

A first baby step was perhaps the Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam in 1990 by the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC). There is much criticism towards this declaration. After all, aside from the critics by Western-inclined human rights lawyers as contradicting the ‘universal’ human rights norms, it still feels like a ‘Western secular meal with a hint of Islamic flavor’. Additionally, as it stands, the Cairo Declaration seems to suggest to be an exception from the rule. However, at the very least, it put Islam on the map of international norms as recognized in the very recent Report of the International Law Commission from its 71st session (2019).

Other important steps include the use of Islamic law principles in international law dispute resolutions. The ICJ case of USA vs Iran case of United States Diplomatic and Consular Staff in Tehran (1980) witnessed a reference towards the Islamic laws of diplomatic immunity. Even more, the Case of Hungary v. Norway case of Gabčíkovo-Nagymaros (1997) witnessed the use of the Islamic legal maxim regarding how harm removal takes precedence over benefit attainment, despite neither parties being Muslim majorities.

Nonetheless, as it stands, these efforts are an underwhelming minority. Salim Farrar (2014) wrote how important it is for the OIC to take a leading role so Islam does not stay in the periphery of international law making. The OIC has 57 members, which is not a majority of states in the world but it is an asset.

Additionally, Islamic teachings, in its epistemology, offers teachings encompassing universal justice for all areas (Al-Attas, 1993). Islam provides fundamentals of environmental preservation (Yusuf al-Qardhawy, 2001), laws of armed conflict (Wahbah Al-Zuhayli, 1998), human dignity and justice (Kasule, 2008), economics (ISRA, 2018), and so much more. Of course all of these fields are always developed to meet the new challenges of time. However, the point is that there is an abundance of materials from which Islam can contribute to the making of International law.

Islam should no longer be a participant, and rather be a leader. Allah says in Surah al-Imran verse 110: “You are the best nation produced [as an example] for mankind. You enjoin what is right and forbid what is wrong and believe in Allah …”. Ibn Kathir (2016) comments on this verse that ‘you’ refers to the Ummah of Muhammad PBUH i.e. the Muslims. He also noted that such praise can only be shared by those who have participated in enjoining what is right, forbidding what is wrong, and believing in Allah. This means that an Ummah worthy of such praise is also an Ummah that should lead in advancements of the world. This should be manifest in all areas, including the making of international law.

Therefore, fiqh al-siyar should be developed in a way to accommodate and encourage this. In the past when inter-state war was a common occurrence, da’wah and conquest was among the ways to open the path for other nations to implement and experience the justice which Islam offers. ‘Universal’ international lawmaking was not present at the time. However, now that inter-state wars are extremely scarce and the ‘doors’ to international law making is open, the extent of how the Islamic nation should approach its relation to the world (i.e. fiqh al-siyar) should also be different. The Islamic nation(s) should enter this ‘door’ and contribute or even take a lead.

SOME PROPOSITIONS

Having all that said, there are a few specific matters which may need to find its way into works of fiqh al-siyar to meet the challenges of the current development.

1. The ‘Ulama should proceed to further develop an Islamic response to areas of concern in the contemporary world.

This can be done by, first, establishing a strong Islamic worldview from which to derive a proper epistemology of knowledge, and, second, making proper blueprints from which to conduct systematic research. The obtained knowledge will be recorded into works from which lawmakers can refer to.

2. The Umara should have a siyasah guideline for participation in international law making.

As of now, it seems that no fiqh al-siyar book (whether classical or contemporary) has discussed participation of Muslim states in international law making, whether in multilateral treaty negotiation, bilateral negotiation, or within international organizations. There needs to be a more comprehensive guide for this not only to prepare the Umara for the negotiation process, but also in how they should coordinate and involve the ‘Ulama following point 1 above.

All the above will need to be compiled, whether in a general compendium together with other subjects of fiqh, dedicated fiqh al-siyar books, or thematic books. It is hoped that this kind of development towards fiqh al-siyar could help face the current challenges of modern international law.

========================

For a PDF version, please download here.